Silver Sparrows' Bat Inquiry

- Ana Furnari

- 4 days ago

- 4 min read

As a teacher at an all-outdoor, inquiry-based school, I get a lot of questions about what and how kids are learning. Most people agree that fresh air, movement, and curiosity are good for children, and yet I still get the raised eyebrow and the careful question: “But how do they do academically? Are they actually learning?”

The answer is an easy yes. I see evidence of learning and skill-building every single day. These kids are creative problem-solvers with a level of independence and critical thinking that honestly rivals some adults I know. And their academic learning is just as strong. It just doesn’t always look like a traditional classroom. Inquiry-based learning doesn’t replace standards. It weaves them into experiences that stick.

Let me show you what that looks like in Silver Science at GAP! This science unit, we have been diving into investigations all about bats. Before we even started, I had a clear set of standards in mind that I wanted learners to practice and build toward. These included measuring mass and length, understanding structure and function in animals, modeling how animals use their senses to gather and respond to information, exploring waves, light, and information transfer, investigating forces and motion, and engaging in engineering practices like defining problems, testing solutions, and improving models. These are core third- and fourth-grade NGSS standards, and they were guiding my planning from the very beginning.

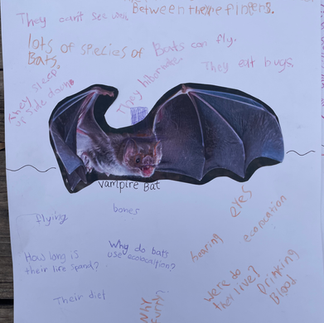

The inquiry started with an invitation. I introduced bats through a simple game where students guessed whether surprising statements about bats were fact or fiction. Debate immediately filled the circle. When answers were revealed, learners naturally began reflecting on what they thought they knew versus what they were realizing they didn’t. From there, we worked in small groups to write down what they believed they already knew about bats and what they were curious about. This was intentionally low stakes. I wasn’t looking for perfectly formed questions, but instead was trying to gauge interest so I could anchor the unit in what mattered to them.

A huge number of their early questions were about bat anatomy, so we started there. We explored structure and function by matching different parts of a bat’s body with what those parts help the bat do. Learners compared bat anatomy to human anatomy through hands-on rotation stations that involved reading, measuring, timing, and observing. We then pushed the thinking further. It’s one thing to compare bats to humans, but how do scientists compare bats to other bats?

That question led us into a bat identification lab. We talked about what kinds of data scientists might collect to identify an animal, then students measured and weighed bat models and compared their data to determine which species they were observing. Learners were practicing measurement, analyzing patterns, and constructing arguments based on evidence, all while doing work that felt purposeful and real.

One concept the students became especially fascinated by was that bat wings and human hands share the same basic structure. I leaned into that curiosity with a guiding question: How and why do bats use their bodies and wings to move through the air? Our invitation was a short video showing scientists uncovering new details about bat flight. After watching, learners shared observations while my co-teacher recorded their words exactly as they said them. Terms like velocity, translucent, scooping, and flexibility came straight from the learners. We then talked about the difference between thin and thick questions and had students write at least three questions they had about bats, with no limits on how deep or imaginative those questions could be. We have done many questioning routines like this throughout the year, and their questioning skills have GROWN! We ended up with way more than 3 questions per learner! Next came one of my favorite moments. As a class, learners read every question and worked together to arrange them from least interesting to most interesting. This step really mattered for us! It pushes learners to engage with ideas beyond their own and recognize shared curiosity. When I collected the questions at the end of the lesson, nine of the highest-ranked questions focused on flight mechanics.

Once again, inquiry and standards meet. Learners were leading the direction, and I was still designing lessons around the science they need to learn in third and fourth grade. After our snow day, learners will return excited to model bat flight using paper airplanes. They will make hypotheses, write predictions, test variables, measure outcomes, and revise designs. Along the way, they will be learning about adaptations, forces, motion, and measurement, not because I told them they had to, but because they asked to. And we’ll continue exploring their questions even after this lab. How could I not use echolocation as the perfect starting point to teach about waves?? And though they may seem silly, “Do bats burp?” and “Do bats fart?” are getting covered too… because comparing digestive systems is such a fun way to discuss body structures and processes!

This is the power of inquiry-based learning. The kids still learn what they need to learn. The standards are still there, grounding the work. But the learning is meaningful, memorable, and driven by curiosity. And most importantly, it builds confident learners who know how to ask questions, test ideas, and fall in love with learning along the way!

%20-%204.png)

This is the first blog post I’ve read in five years, and now I’m going to have to go back a read them all. I’ve always known you guys are amazing educators, but it’s just so thrilling to read about a professional being so dang good at what they do!

Also though, “after their snow day,” as in singular day, did make me lol.